I made my directorial debut for community theatre doing Qui Nguyen’s She Kills Monsters. This is my absolute favorite play, I had long been hoping to put it on one day. When I finally got the opportunity, I was absolutely thrilled– and startled by the sheer amount of work this meant I needed to start on, pronto!

She Kills Monsters is about two sisters getting to know each other (with a twist) through playing Dungeons and Dragons. Like many of Qui Nguyen’s plays, this one is action-packed, full of fighting and off-color humor. The main character, Agnes, and the rest of her party fight against swarms of classic D&D baddies. Creating these monsters can be a real challenge.

Since the show is so popular, I thought others might find it helpful to hear about my process!

First Trial

Initially, I wasn’t sure how exactly I would pull off these monsters… but I’ve always been a crafty person, and I started making plans for my monsters early on (before I even officially knew I’d be directing the show!).

Discovering Wintercroft LLC marked the moment that I knew I could put this show on, even if I didn’t have a dedicated costumer.

Wintercroft designs papercraft templates for masks, jewelry, and home decor. Their masks are really remarkable. The templates are mostly quite easy to assemble (the site provides a difficulty rating and crafting time estimation for each mask– some are harder than others), and very cost effective. The templates generally sell for under $10, and once you own the template, you can print it as many times as desired. The masks themselves are constructed out of thin cardboard (think cereal box material) and glue.

Instead of buying Halloween monster masks at $10-30 bucks a piece (or more), you could hypothetically craft a whole group of monsters for no more than $15 (one template printed multiple times, made with some cereal boxes you scavenged from your pantry, and add the price of some glue sticks).

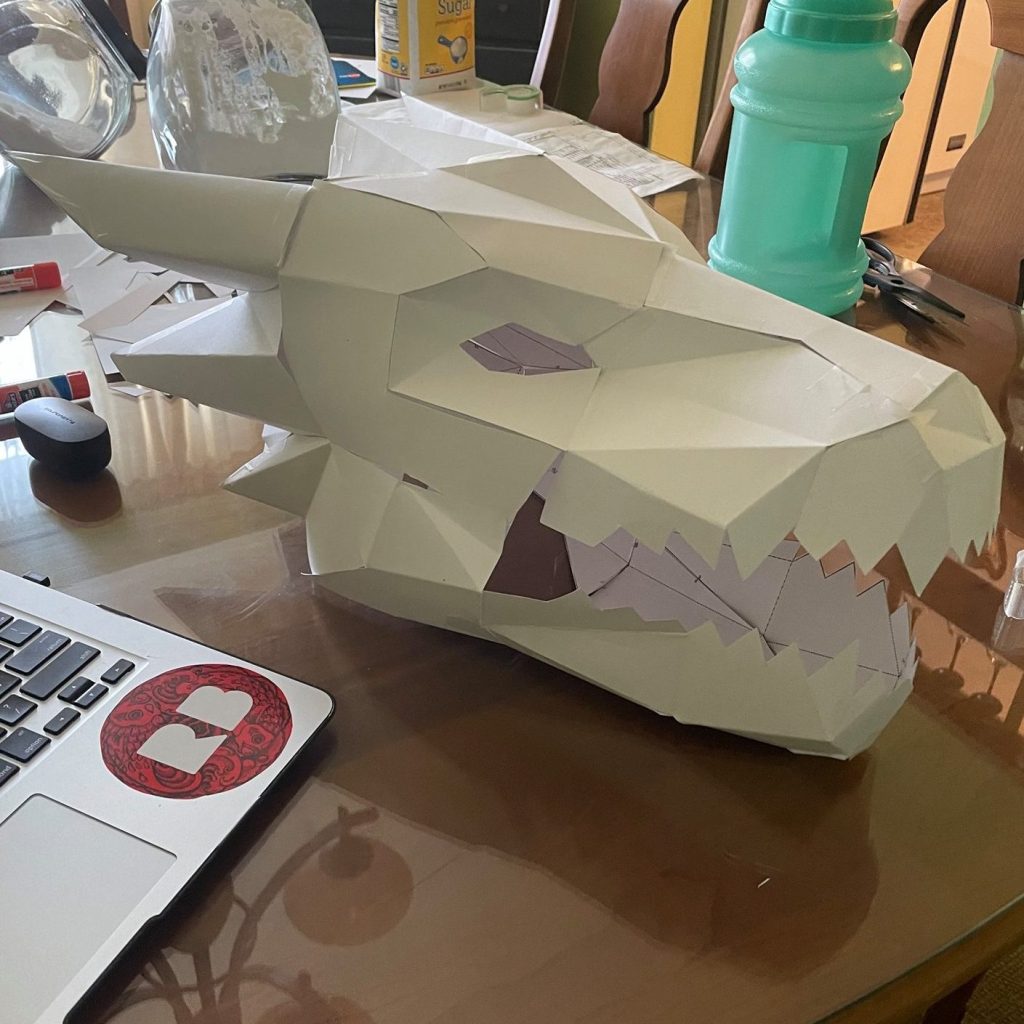

To test out the process, I decided to use Wintercroft’s Dragon V2 mask as a trial. The process was a lot of fun, and turned out looking pretty good. My mistakes with this first test were using cardstock instead of thin cardboard, and opting for the “untabbed” construction method (explained in the template files), which both created a much floppier final product than I was hoping for.

(My first trial went pretty well, and looked pretty cool, but I had hopes that switching up my method would have even better results.)

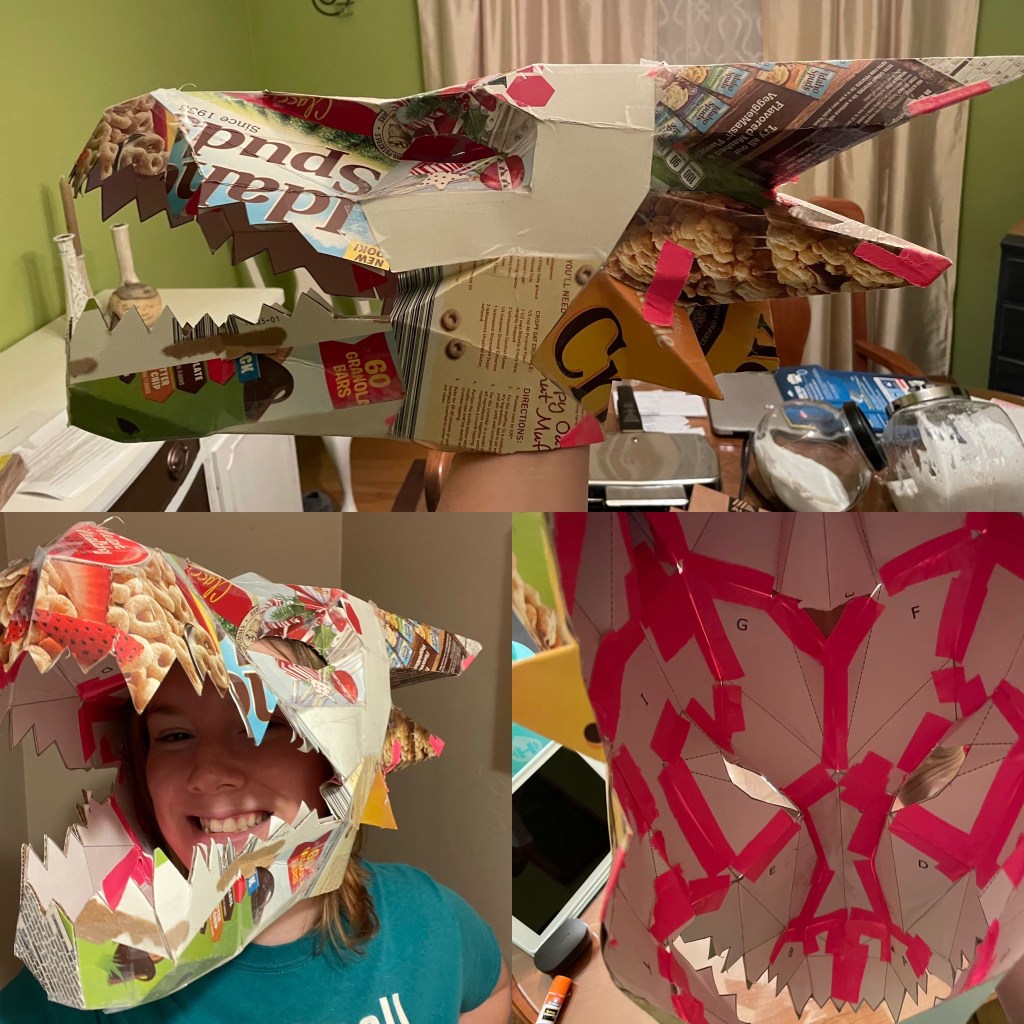

So, I went back in for a second test-run, this time using cardboard and trying the “tabbed” construction method.

The basic process, in a nutshell: You print the templates on paper, cut them out, glue them to the cardboard, cut those out, and fold all the pieces on the dotted or dashed lines as appropriate (the templates explain all this, too). Then you use the matching numbers on the edges of the pieces to put the whole thing together, like a puzzle, gluing as you go.

(Some pictures of my second attempt. I used card for this one and had some help from duct tape. Bottom right shows you what the inside of the templates look like– there’s tape over the numbers that show you what piece goes where, but as you can see, the pieces are also lettered.)

This version was a lot sturdier, but I was still a bit unsure of how this would hold up for performance, especially during fight scenes or in the dark backstage. I had horrible visions of someone dropping their mask and stepping on it in a rush.

In searching for solutions, I found this video from Ultimate Paper Mache, explaining the process for super sturdy, quick-drying paper mache using brown paper bags and a specific brand of wood glue. It seemed like exactly what I needed! I’d never done paper mache, but the process seemed really simple (and fun), so I decided to give it a try.

I invested in some wood glue, ripped up some paper bags, and got to work. The process was easy, I just did exactly what the video said– the most time-consuming part was just waiting for the paper mache to dry. I found it seemed the most sturdy after about 24 hours of drying. Materials-wise, I found heavy paper bags (think grocery bags or food delivery bags, like you get from Chipotle or McDonald’s) to be better than paper lunch bags.

One coat of paper mache was pretty solid, but I decided to try doing more to see how sturdy it could get. I did a test with one coat of paper mache on the interior of the mask and two coats on the exterior, and the result was SO sturdy that these masks felt borderline indestructible. For good measure, I sealed everything in with a clear coat of mod podge.

With these tests done, I figured Wintercroft was a really good option for my monster needs. I sent the company an email to ask if it was okay to use their masks in a theatre production, and they gave me the go-ahead! On to phase two…

Plans, Designs, and Further Tests

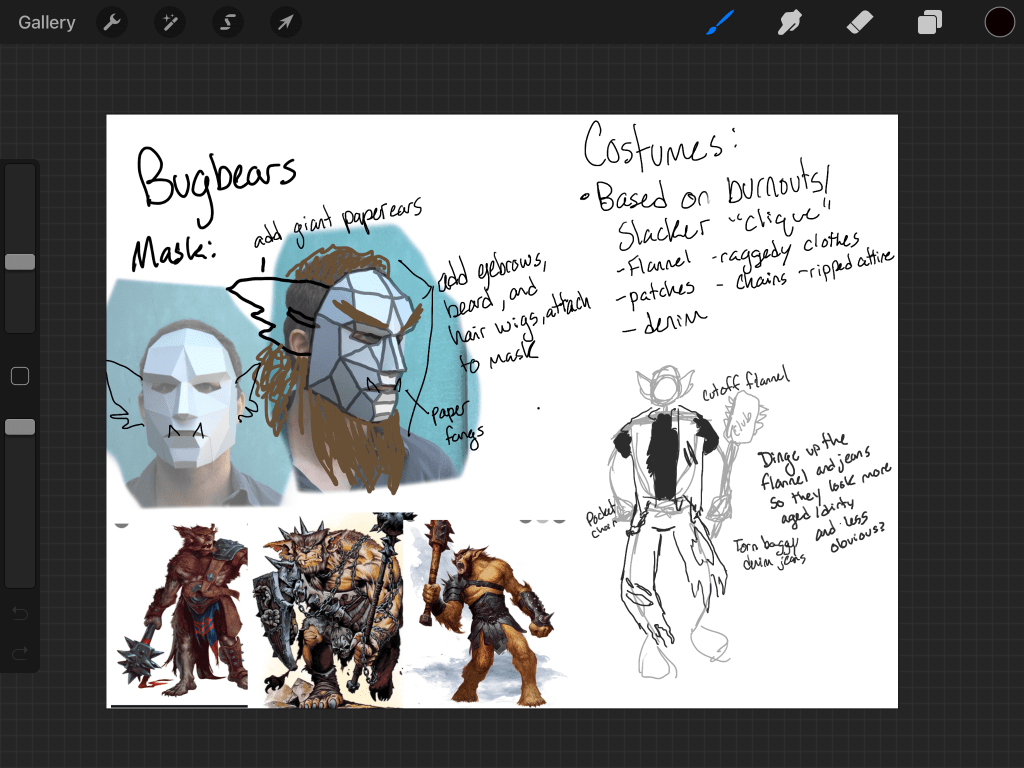

I started searching for Wintercroft templates that I could use to create the various monsters for the show. Of course, Wintercroft didn’t really have the specific creatures I was looking for, but I was excited about the prospect of using additional cardboard, paper, and mixed media details to really make the templates my own. Using Procreate on my iPad, I started drawing up some plans.

(As a sample, this was the plan for the Bugbears, which ended up being my favorite monsters! I ended up simplifying/changing quite a few elements from this first design, but those mask add-ons are exactly how the final product turned out.)

I decided to try out the process of modifying the masks, so I got started on some Bugbears.

I repeated the same process I did with my test dragon. I made the masks, covered them in paper mache, and sealed everything with mod podge. Then I painted them, sealed the paint with more mod podge, and got started adding some additional details. The teeth were as simple as cutting triangles out of extra cardboard and glueing them into the mouths. I decided to make the ears out of EVA foam (not really sure why when cardboard would’ve worked just as well… but that was also as easy as cutting out shapes and painting them, for the most part).

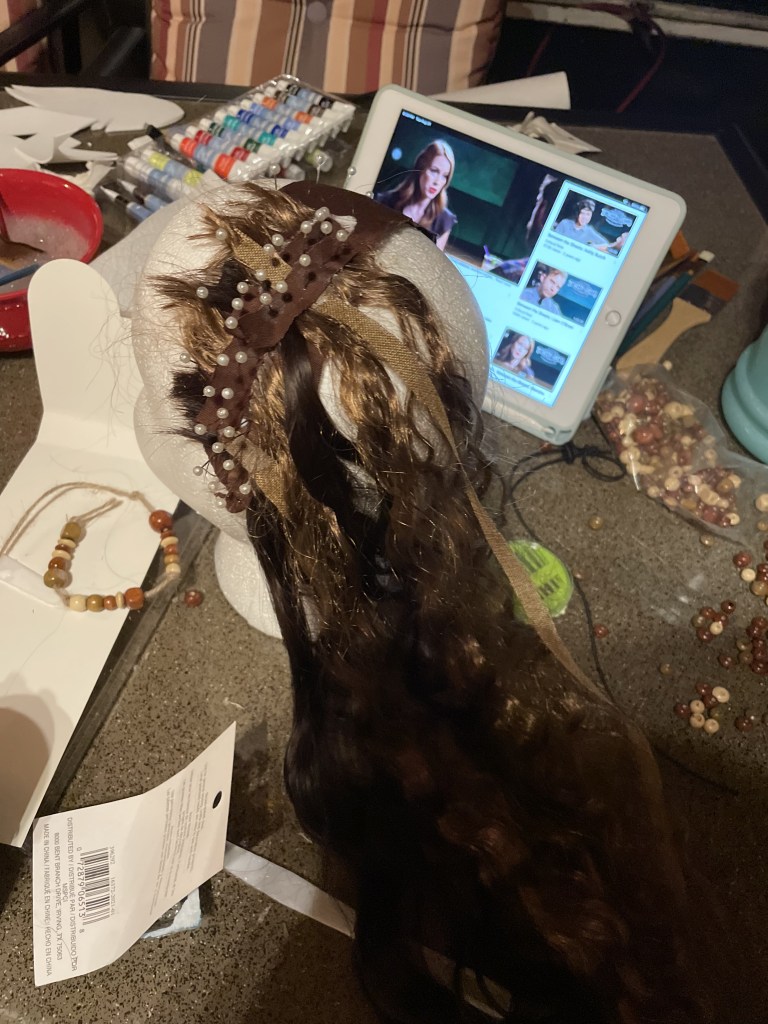

I decided to get a little more ambitious with the hair pieces. I bought a number of crappy “ponytail extensions” on Wish, all slightly different textures and colors. I handmade a wig for the mask by cutting locks of hair off these extension and gluing these individually to a strip of fabric. I alternated different styles and colors of hair to make the wigs more “wild” and unkempt looking. I also added some lengths of twine (and put some beads on some of these, just for fun) and some strips of different fabrics, to help break up the texture. I liberally applied more glue over all of this and put another piece of fabric down over the top, so I had a sort of hair-fabric sandwich– then, once this was dry, I attached it to the top part of the mask using velcro pieces. I wanted the wigs to be removable, just in case. I repeated this process but with shorter pieces to create beards.

(Miscellaneous process photos of my Bugbears. These were SO FUN. The wigs took a stupid long time, but it feel like the final result was so worth it.)

These turned out pretty much exactly how I’d pictured them, so I was confident that my plans were going to work out. Now I just had to make a whole lot more.

Lots and Lots and Lots of Mask-Making

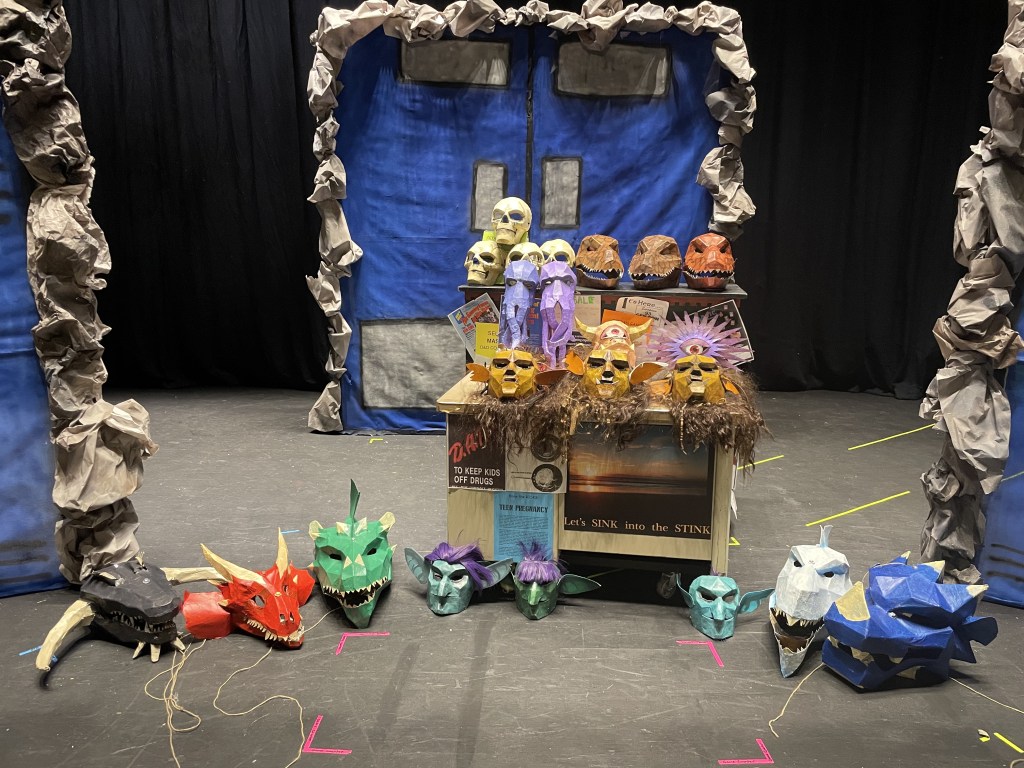

I finished my planning/designing process and tallied up my monster count: 3 goblins, 3 kobolds, 3 bugbears, 4 liches, 2 mindflayers, a cyclops, and a beholder. I also needed 5 dragon heads for Tiamat (which will be its own post in the future). This was a total of 22 Wintercroft masks. Wintercroft’s website suggests that their masks take somewhere between and hour (for easy masks) to 8+ hours (for hard masks) to build… and that was just to build the mask itself, leaving aside time to paper mache, paint, and adapt the masks to suit my needs. AND that also didn’t account for the rest of the monster’s costumes: the mask was only supposed to be one part of the whole outfit!

Mask-making became a pastime not just for me, but for my whole family, and on a few occasions for some of my co-workers, too. The process of cutting the templates out, gluing them to cardboard, and then cutting the cardboard pieces was so simple that anyone could do it. I was lucky to have a number of helping hands for this step.

The actual assembling of the masks was time-consuming and lot more complicated, so I primarily did this myself. (I had some help to finish assembling the last 2 or 3 at a set build during the rehearsal process– big thanks to my volunteers!) This step took me about a year. My bugbear tests were in September 2021, and I continued to work on masks until the month of the show, November 2022. To be fair, a lot of the construction happened after summer 2022 and was crammed into those few final months, so it’s not like I was crafting nonstop for 14 months.

Some tips and tricks for working on Wintercroft templates I picked up during this time:

- If you’re making a lot of creatures, be prepared to gather a LOT of card. You can scavenge this from a LOT of food and household products. Cereal boxes, frozen pizza boxes, tissue boxes— anything along those lines. You want the boxes to be in good shape (not crumpled up/folded). I explained to my coworkers what kind of cardboard I was looking for and asked them to save theirs for me— I ended up with a ton!

- I said above that the “card” the templates call for is NOT the same as cardstock. Cardstock could possibly be used for some small details, though— just not for big, structural shapes. If you’re really struggling to collect enough card, you could possibly experiment with this.

- I found wood glue to be a really good adhesive when glueing the pieces together. It dries fast and solid. You only need a tiny bit. Use less glue than you think you need, and use your finger to smear it flat on the tabs, so it doesn’t take so long to dry. Glue sticks also work, but maybe not as well.

- You have to hold the pieces together while they dry. I found paperclips and chip clips really useful for this— you could glue a piece, throw a chip clip or paper clip onto the spot you’re trying to get to stick together, and set that aside for a minute to dry while you worked on a different piece.

- I found a combo of glue and tape to be useful— the tape helped to keep the pieces solid while the glue was still drying down. When I started getting really impatient, I tried to use a stapler when sticking pieces together. I feel like glue and tape/staples together work better than just staples or just tape. I wouldn’t use staples on a mask that has to fit close to the face, though, for fear of someone getting scratched or poked!

- In general though, a lot of the mask-making process is just waiting for glue to dry. Podcasts and 8-hour YouTube videos were my best friends during all-nighter crafting sessions.

- These templates are very adaptable! You can modify elements of the templates, or Frankenstein some together in some interesting ways. You can also get creative with mixed-media experiments to create some really cool results, like I did with my bugbears. Don’t be afraid to experiment and work with your own ideas. Even a good coat of paint can totally change the vibe of a mask.

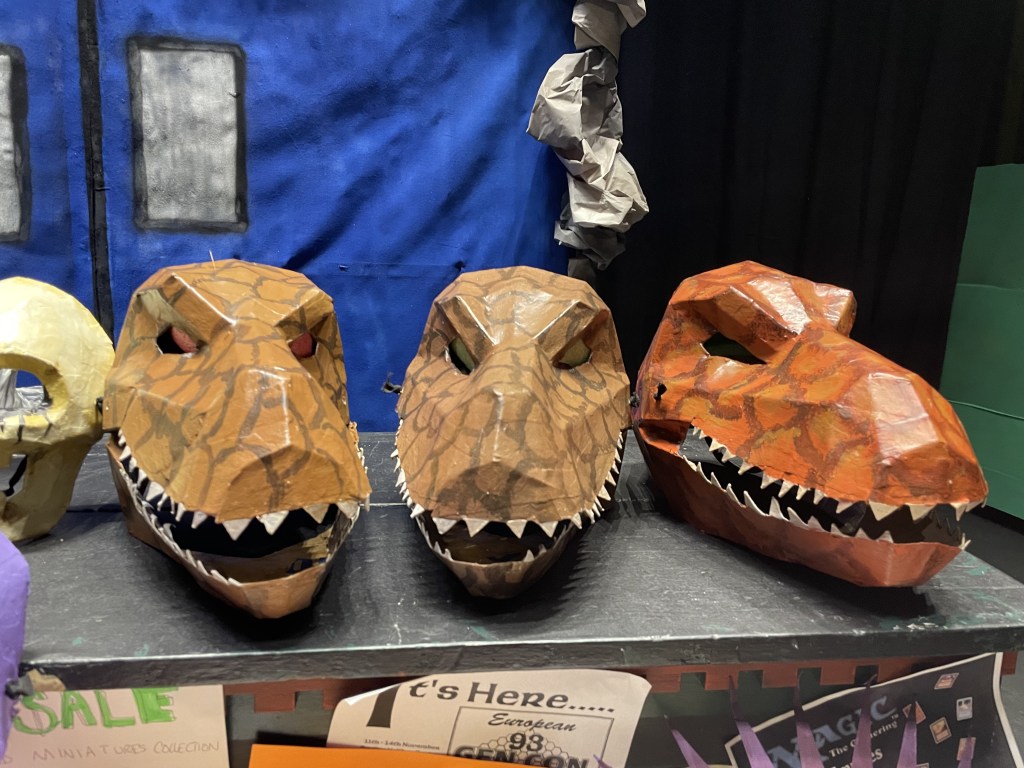

Here are some photos of all of my finished Wintercroft monsters:

Here are links to each of the templates used:

- Liches – Death skull (hood piece omitted) x3

- Kobolds – Velociraptor x3

- Bugbears- Polygon face mask v2 (with wigs, ears, and fangs added) x3

- Goblins- Witch mask (with wigs and ears added) x3

- Mindflayers- Cthulhu x2

- Cyclops x1

- Vera the Beholder- All-seeing eye x1

- Blue dragon- Dragon v1 x1

- Green dragon- Dragon v2 x1 (with an added head-fin)

- Black dragon- Crocodile (with modified horns from Kapros added!) x1

- Red dragon- The awakener dragon skull x1 (with added fins)

- White dragon- T-Rex x1 (lots of slight modifications to the template for this one)

This was a boatload of work. I can’t say I regret it– I did have fun assembling all these! If I were to do it all again, I would finish more of the construction in advance (cramming most of the work into the last few months before the show was a bad call, lol) and probably enlist some more help.

Garments and Final Touches

Masks were not the extent of my monster plan. Unfortunately, they were much more time consuming than I was expecting them to be, so I SORT OF ran out of time for the rest of the costumes.

My plans for the rest of the monster costumes weren’t elaborate, anyway. Many of my monsters would need to make some pretty quick changes (I planned my cast so Evil Gabbi and Evil Tina played 5 different creatures each through the course of the show), so I wanted to go pretty basic, anyway. I simplified my original plan so that, generally speaking, each monster costume was a mask plus one or two other garments at most. The “base” for each monster costume was a plain black shirt and black pants so that other elements could be added on top.

Since Tilly draws on her high-school trials and tribulations to create her adventure (the Succubi are her cheerleader nemeses, and her guidance counselor appears as a Beholder), I decided to lean into this and make give each group of monsters a classic teenager archetype. As it happens, I work at an escape room that was getting rid of a locker room themed game, so I scored a number of sports jerseys that they were going to throw out. Pretty much every other garment we used came from either Goodwill or clearance Halloween stores. We got a few finishing touches from Amazon.

The kobolds, pack-hunter lizard folk generally considered to have less-than-average intelligence, were a perfect fit for the “jock” stereotype. I cut apart the football jerseys I got from the escape room so that they resembled basketball jersey-tanks. The kobolds also got sweatbands for their wrists. Since I had the football jerseys, I decided to make my cyclops into a football player– it seemed appropriate, since I planned on making the cyclops the “big boss” of the fight montage at the end of scene 5.

The big, hairy bugbears were grungy burnouts, a la Judd Nelson in The Breakfast Club. They got some flannel shirts from Goodwill. The skull-faced liches made perfect goths– long black cloaks for them. We made the goblins punk-rockers and gave them each a denim vest.

All the garments got some artificial aging with the help of some sandpaper and spray paint.

(These are the best two photos I have of my monsters– Vera the Beholder and the cyclops. Photos by KGTunney Photography. I have a few other photos, but they’re just low-quality rehearsal snaps. You can see the football jersey I got from the escape room on the cyclops.)

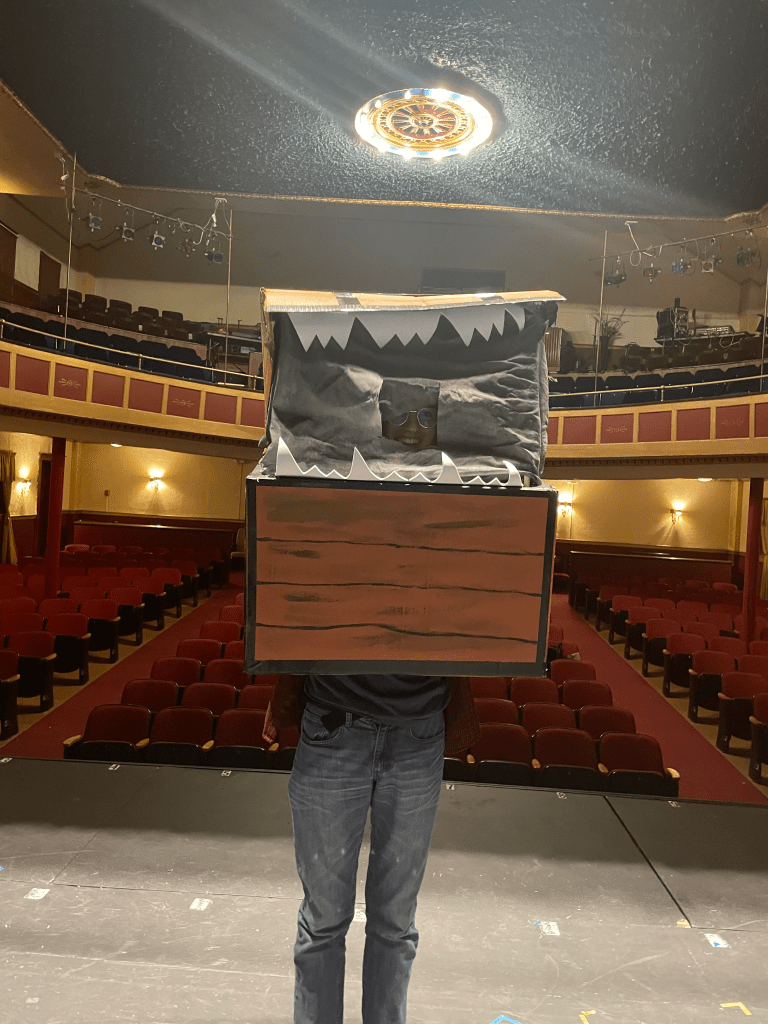

22 monsters down, I decided I wanted to add one more. This allowed me to add DM Biggs to the fight montage, and I thought it would be more fun if everyone got a turn to fight… so at our final few set build days, we speed-built a silly mimic costume out of a cardboard box. It figures that the monster we spent the least time on was probably the biggest crowd favorite.

(A work-in-progress pic of the mimic, and a photo of it more or less completed. I had almost nothing to do with the construction of this one besides saying I wanted it and bringing a box. Thanks, volunteers!)

The mimic was such a hit that I do wish I’d been a bit more creative with the rest of the monsters. The masks were really cool, but a lot of work, and a cardboard box with legs delighted the audience just as much if not more!

Final Thoughts

I still can’t bring myself to regret all the time I spent frantically building monsters. It was a lot of fun! If I did it all again, I’d get more creative– and either start a lot earlier, or get a dedicated costumer instead of trying to do it while also directing. (Or start a lot earlier and with a dedicated costumer… both is good!)

If you’re looking for a resource for making cheap and impressive monsters, Wintercroft is such a great resource– I can’t recommend them enough. Besides the theatrical applications, they’re just fun art projects, and they also make great halloween costumes. If you want to use their masks in a production, just email their support to ask for permission, and be sure to give them the credit that is due!

Happy monster-making!– I’d love to see some monsters others have made in the comments.